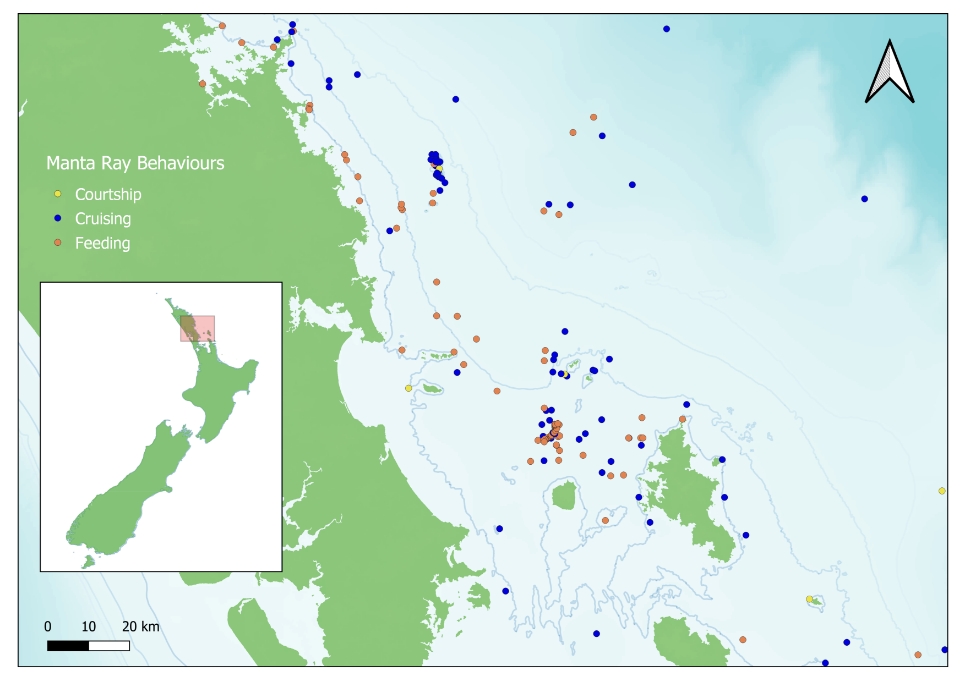

The Manta Watch team define a hot spot as an area or specific location that has experienced consistent manta ray activity over time.

These potential hot spots are identified as we continually update our sightings records, which we gather through real time citizen science submissions and by conducting dedicated manta ray surveys.